This is the second part of the series of John’s articles on Storytelling in Concept Photography. You can find Part 1 and Part 3 of the series here:

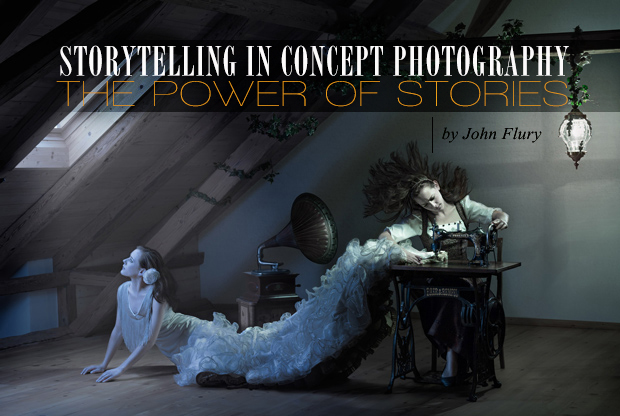

Storytelling In Concept Photography. Part 1: The Power Of Stories

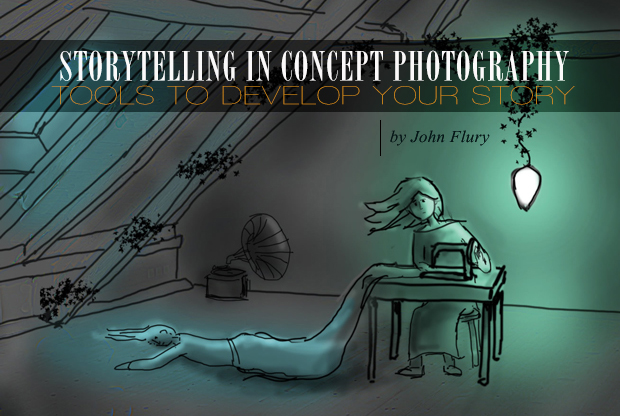

Storytelling in Concept Photography. Part III : Tools to Develop Your Story

Enjoy!

In this second part of the trilogy, we’ll have a closer look at the basic ingredients of a good story. It’s not surprising that these apply both to literature, film, and photography, since the fundamental function of a story is always the same, regardless of the medium used.

The Conflict

One of the key ingredients for a good story is the conflict. In the majority of stories, the conflict describes fairly well what the story is actually about. It creates tension, drama, and depth. Any neuroscientist will attest that there is a strong association between stress and relief. This means that even if the storyteller decides not to unveil the resolution, it is nevertheless present in the listener/viewer/reader’s mind. That’s one of the reasons why conflicts are such an important and powerful tool in conceptual photography; the conflict will continue inside the mind of the viewer, who will then try to find a way to resolve it.

There are many types of conflicts and they are almost always bilateral, with the protagonist on one side, and opposed to him, his enemy: society, a force of nature or even another side of himself—a so-called inner conflict.

Inner conflicts are easier to write about than to show. This is especially true for cinema, in which the viewer expects to be entertained passively. The photography medium allows for more subtle cues about the character’s inner life, because the viewer can choose how long he would like to absorb an image and let the story sink in. In some cases of contemporary photography, the level of subtlety is definitely commensurate with literature.

So, whether you’d like to create a photo with a message/story that’s readily understandable for all viewers the second they see it, or you’d like to add more symbolic, hidden layers of truth, the decision is a matter of personal preference and target audience.

As a mental exercise, think again about the photo I asked you to remember and try to find its conflict. Has the maker of that photo provided a resolution? Does the story continue in your head? Are you hearing voices in there? If so, it’s quite possible you’ve gone ’round the bend. In which case, I apologise and urge you to call a shrink. 🙂

The Sequence of Events

All stories have a chronological order, represented by a chain of events through which the story logically progresses. It might not be the order the narrator chooses to present his story. In literature, we often see the linearity broken and later events presented earlier as a means to create further tension. But the chain can always be reconstructed. So how can we form a sequence of events with just a single photo?

The Climactic Moment

The climax of a story is the turning point where an important balance in the story tips over. Unarguably, the most important way to condense a sequence of events in a story is to show its climax. Here are some examples to illustrate these so-called twists:

- the protagonist finds the truth – The Truman Story

- the powerless becomes empowered – Cinderella

- the lonely connects to another human being, be it a friend or someone he falls in love with – Wall-E

- the imprisoned or restricted becomes free – Braveheart

…etc.

Sometimes in photography, the moment before or after the climactic moment is actually even more interesting, because it will tell the story even better photographically and still work as well as the climax. I will present an example of this at the end of this article.

Juxtaposition

Another tool for condensing a story is temporal juxtaposition – showing the protagonist in different stages of their journey. A classical visual example of a juxtaposition would be the progression of the human species from the crooked form of our ape ancestors to the homo sapiens (and possibly to Gregory Heisler; this guy just can’t be on the same evolutionary stage as the rest of us!), all shown in sequence.

The following example project is actually a variation of the temporal juxtaposition. Here, the sequence of events isn’t shown by just a single person, but by different ones. There are still enough visual similarities to keep them visually connected.

It’s the story of three fairies who are captured inside lamps and used as a cheap light source by human folk. Each fairy depicts a different notion: The fairy on the right depicts despair, the one on the left, hope, and the one in the middle, deliverance. While they are different persons, they also represent a temporal overlap of emotions and actions. The middle fairy represents the actual climactic moment in our sequence of events, whereas the other two show the states of conflict.

Click to enlarge:

The Inner World vs. The Outer World

A character’s environment, his own actions and those of his peers constitute his outer world. The inner world consists of his own thoughts, memories and, most importantly, his emotions.

When talking about conflict, giving the viewer access to the protagonist’s inner world in a non-literary medium such as photography and cinematography can be a challenge. I feel that I have only yet begun to find ways and the visual language possibilities to unlock a character’s inner world, but here are some of the approaches in common use:

1) Facial expressions and body language

The most direct form of conveying emotions visually!

By the way, don’t tell your models to “look sad”! Tell them the story they are part of and, if possible, let them perform an action with their hands.

I’m sure most of you know this instinctively — emotions cannot be expressed convincingly in a vacuum, they need some soil to grow from — a story, an action, an object, etc.

2) Direction of sight

A person’s eyes can convey a wide range of emotions and intentions just by the direction they look. A person could be looking at an object or person that they have strong feelings about (fear, love, hate).

As such, the eyes can help build relationships within the photo. But also simply looking up or down can express feelings like shame, a state of intense concentration, or an attempt to remember something.

3) Movement

The direction from which a person is coming will inform the viewer about what just happened or, by abstraction, what the character’s past might be.

Conversely, the direction toward which he or she is heading enables the viewer to partake in the characters intentions and, with some imagination, his future.

4) Inclusion and exclusion

You choose what your image will contain and what it will not, which will influence whether a viewer will sense the character’s intention and focus. Exclusion can be a wonderful story element as well, with endless creative possibilities.

5) Color concept

Colors help to support the mood of a photo, which should coincide with the mood of the person(s) shown. I personally like to stick to a two- or three-color palette, so that each can be more expressive with regard to the story.

6) Depth of field

Similar to the inclusion and exclusion bit, your story should drive where your image is sharp and where it becomes blurred. Images shot with a very wide aperture (shallow depth of field – editor’s note) can help create a sense of isolation or increase the sense of spacial depth, making a room seem larger than it is in reality.

7) Composition

I don’t mean the numerous standard rules/guidelines for composition, but the visual balance of key elements within the frame. Try to think about what the most important element is and leave enough room for it in the photo. In my last example, the main character was not only defined by her center position, but also by her slightly raised position in the frame.

8) The surreal (my personal favourite)

Another technique to represent the inner world is to blend reality with the surreal: dreams, visions, wishes, fears, forebodings. The more seamless the fusion of the two appears, the more potential impact the image can have on the viewer.

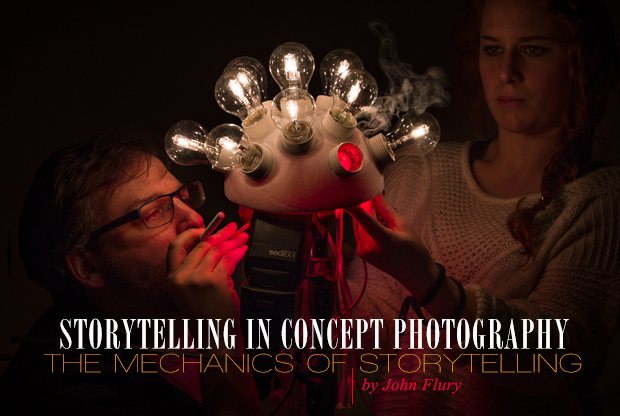

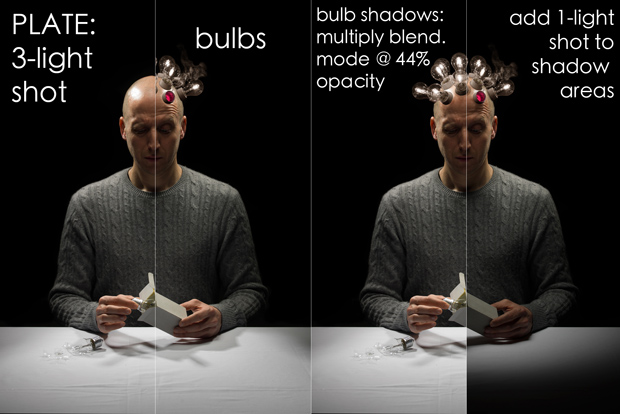

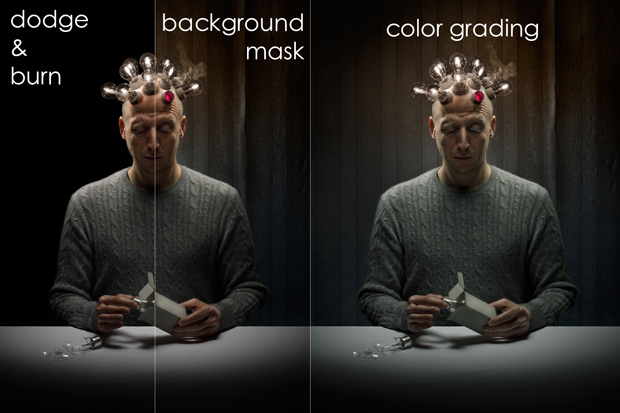

I’d like to demonstrate this with one of my recent projects called “The Smart Man”.

“The Smart Man” is the story of a genius. Being smart isn’t something one is without effort; it’s the ability to actively recover quickly and efficiently from mistakes, learn from them, and become wiser. The light bulbs are obviously the surreal element here, which represent the individual ideas of the genius.

So, the lighting here is not just helping to tell the story, it IS the story.

Click to enlarge:

The actual climactic moment would be the one where the light bulb bursts. But as I’ve written above, photographically, this climax can be presented more successfully by showing what happened right afterward. The smoke rising from his empty socket and the broken bulb on the desk are enough information to tell the viewer what happened.

The full tutorial on this project can be viewed on my blog: Tutorial: The Smart Man

In the next and last part of this series, I will review some of the tools that can help you develop your stories.